This is a breakdown of the film’s “reality” — the part hiding beneath the dream. No mysticism, no conspiracy. Only the way Lynch himself invites you to assemble the story: through details, repeated objects, and traces the dream can’t fully erase.

Who Diane Is Before Hollywood

Diane Selwyn arrives in Los Angeles not as “just another dreamer,” but as someone who has already tasted victory. Before the opening credits comes the jitterbug: people dancing while their shadows live behind them. It’s not cute retro décor — it’s the first instruction. In this film almost everyone has two versions: what happened, and what the mind invents so it doesn’t die from pain.

Among the dancers is Diane herself. Nearby is the elderly couple — the contest “judges.” In reality they feel like a blessing: you won, you’re worthy, the world is open. That’s why their later transformation is so horrifying — when blessing turns into sentence.

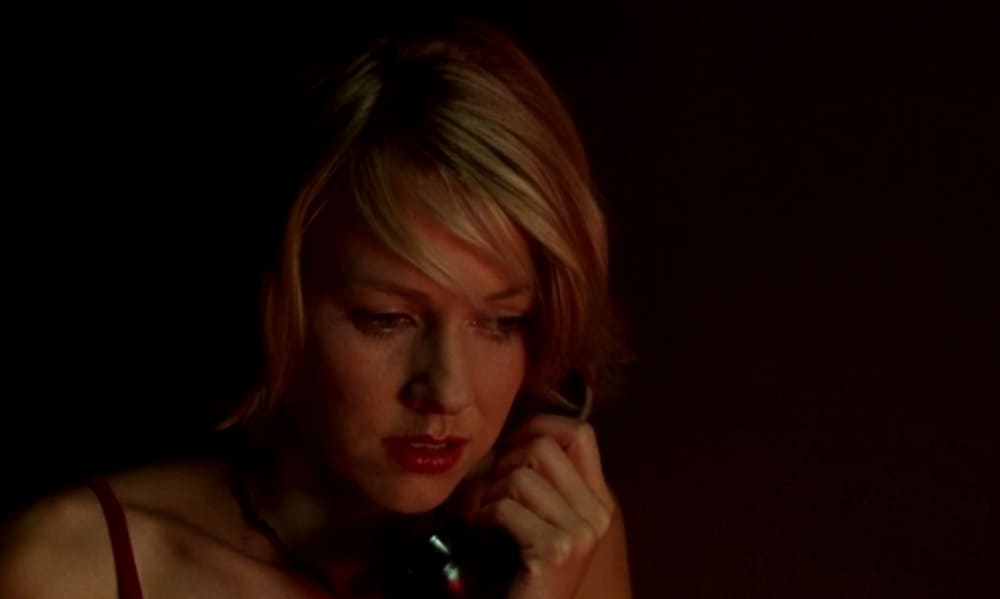

Then comes the key moment Lynch shows almost physically: the camera drops with Diane onto the pillow, as if we see it through her eyes. It’s the “sleep mechanism,” triggered by overload.

The real foundation is simpler and harsher: Diane has Aunt Ruth. In reality Ruth has died and left Diane some money — the ticket to Hollywood. That’s why, in the dream, Ruth comes back to life: Diane’s gratitude won’t let her “release” Ruth, so the dream turns her into protection, not memory.

Hollywood Reality That Doesn’t Forgive

Los Angeles doesn’t greet Diane with a red carpet. It greets her with what Hollywood does best: promise the same thing to everyone, and give it to a few. Life is poor, the apartment is bleak, auditions pass her by. Where her mind wants a montage of “success,” reality gives her a montage of “rejections.”

And here the film’s real needle appears: the project The Sylvia North Story. Lynch practically underlines it: notice the title, where it’s said, where it repeats. In reality the film is directed by Bob Brooker, Diane goes for the lead, but the role goes to Camilla Rhodes. For Diane it’s not just a job lost. It’s the moment the dream gets a face: “that’s the one who gets everything.”

In the dream the title remains, but the director changes: Adam Kesher “gets” it — the man who, in reality, becomes the instrument of Diane’s final humiliation. The dream carefully moves blame to where it “belongs” inside Diane’s emotional system.

Camilla: Love, Dependence, Humiliation

Camilla and Diane grow close. The paradox: at first Camilla isn’t an enemy but a guide. She helps Diane land small parts, keeps her afloat in an industry where loners sink fast. It can look like friendship, but inside Diane it quickly becomes dependence: Camilla is both “love” and “the door to Hollywood.”

They begin an affair. And here Lynch does something especially cruel: he shows not only passion, but the status gap. Camilla is always a step ahead — more talented, more confident, more “legitimate” for this world. Diane is beside her, yet somehow at the edge of her own frame.

That’s why the breakup isn’t merely painful — it’s annihilating. Camilla begins a relationship with director Adam Kesher and tells Diane it’s over. Diane rages, throws Camilla out — and still accepts the party invitation. Not because she wants to, but because she can’t do otherwise: dependence is stronger than self-respect.

The Party as the Breaking Point

The party is a real scene that later becomes the quarry for the dream: the dream will haul props, lines, faces, even intonations from here.

Lynch’s prompt is precise: watch the red lampshade and the phone. In reality, the invitation call is bad news. In the dream it becomes the danger signal — the one “puncture” where reality pierces illusion.

Diane arrives and enters via the short path. A small gesture that works as symbol: a short way is a fast way into trouble. From this point the film stops letting her turn away.

Then comes everything that finishes her:

- Camilla and Adam announce their engagement.

- Camilla kisses another woman — and a promise of a role hangs in the air.

- Coco (Adam’s mother) drops a line that will echo later, in another plot and another “reality,” like sound bleeding out of a dream.

- The Cowboy appears — seemingly “just a guest,” but in structure he becomes the voice of fate. Even his look matters: missing eyebrows make him unsettlingly inhuman, a sign he’s not quite a “character” but a function.

Another anchor: the pearl earrings. In reality they’re on Camilla. In the dream a cop asks, “Is any girl wearing pearl earrings?” — a seam that stitches the worlds together.

At the party Diane receives the core truth: not the fact of the breakup, but humiliation. She’s forced to watch herself being erased.

Winkie’s and “Joe the Hitman”: The Point of No Return

After the party she goes to Winkie’s — a place Lynch uses as a “decision chamber.” In reality Diane makes her choice here. In the dream it becomes a gate for horror and conscience.

Across the table sits Joe the hitman. Diane pays and puts down a photo: “This is the girl.” In those four words is tragedy: after that, any explanation becomes justification — and justification doesn’t save you.

Joe promises: when it’s done, Diane will receive a blue key. Not a “puzzle clue.” A receipt. Material proof after which she can’t tell herself, “maybe it’ll be called off.”

Nearby stands the young man Dan at the counter. What matters isn’t who he is, but that Diane’s gaze catches him. In the dream Dan becomes “doubt” — something fear must kill so the decision stays final.

Then reality closes in: at home Diane tries to mute guilt — with the body, with fantasy, with anything. Then comes the call: “it’s done,” and the blue key appears. And the mind is left with one escape it can afford: sleep — rewriting what happened so she can survive a little longer.

The Final 30 Minutes: Reconstructing Truth by Props

Lynch gives a simple tool: the last real-life scenes are scattered out of order. You rebuild them like a forensic tech — by objects.

The piano-shaped ashtray on the table belongs to the time when Camilla and Diane were still together. It’s not “art symbolism.” It’s a domestic timestamp: “it was still warm then; not everything was ruined.”

The white robe and the coffee cup are near the end. These are the latest moments: Diane wanders the house, empty-headed, torn inside — minutes before suicide.

Another splice: Winkie’s coffee cups. They exist in reality and in the dream. As if the film says: you can swap faces, rename people, reshuffle roles — objects will still remind you where the decision was made.

There’s also the chilling marker: the sense the apartment has “shifted,” things aren’t where they belong. The dream tries to rescue; reality drags her back to the point.

When guilt no longer fits inside, it starts walking the house on its own: the elderly couple — those “judges of success” — return as tiny pursuers, guilt made flesh. And “the man behind Winkie’s” — inner evil — locks the key in the box, as if signing the verdict: that’s it, it’s part of you now.

The final conclusion

Strip away illusion and Mulholland Drive becomes terrifyingly simple.

Diane arrives in Hollywood with the myth of victory. She loses. She falls in love with a woman who is both support and unreachable peak. She’s humiliated at the party. She orders a murder. She receives the blue key as a receipt. And then she understands she didn’t kill a “problem,” she killed the last support of her own self.

So “Did Diane kill Camilla or herself?” isn’t metaphor or game. It’s one story stretched over time.

She kills Camilla — and by that act begins killing herself.

That’s why Lynch ends on Silencio: after such a decision there are no explanations left, no justifications, no music. Only silence.

5 scenes to rewatch after reading

- The jitterbug before the credits (and the shadows in the back)

Don’t watch the dance — watch the film’s “rule”: double roles, the real person and their invented version. Memorize the elderly couple’s faces — later, it won’t feel innocent. - The first-person fall onto the pillow (yellow bedspread in frame)

This isn’t just a transition. It’s the entry point into the dream. Rewatch it as a “technical moment”: breathing, camera angle, the sensation of collapse — then compare it to the final real-life minutes. - Adam’s party: the “short path,” engagement, kiss, and the Cowboy

Rewatch it as a warehouse of future nightmares: echo-lines, micro-details, the pearl earrings, the Cowboy as a figure of fate, and how the camera holds on Diane — as if she’s already outside her own life. - Winkie’s: “This is the girl” and the promise of the blue key

The scene where the film stops being a puzzle and becomes a verdict. Notice how ordinary the line sounds — and how that ordinariness carries finality. - Silencio: “No hay banda,” “Llorando,” and the appearance of the blue box

Rewatch it as the moment illusion confesses it’s illusion. Everything matters: the “recording” reveal, the real pain in the voice, and how the world simply shuts off after the box.